TR Review: Ex Machina Is a Very Human Look at Robots

|

Ex Machina is perhaps one of the nerdiest films ever made, as it began as a way for writer-director Alex Garland to win an argument about the Turing test (for those who missed The Imitation Game, it’s a test to see if a machine can make you believe it’s human) with his friend. What would it take, he wondered, to win that argument? Well, in part…it takes a topless robot, apparently. So how can we not love what he’s come up with?

There certainly could be ways. As a screenwriter, notably of such Danny Boyle films as The Beach and Sunshine, he doesn’t always nail the ending, to put it mildly. But freed from Boyle’s ever-more-persistent need to be frenetic and over-showy these days, Garland takes a minimalist approach that’s refreshing, and without spoiling things I can tell you that his ending here is solid, even if I might have cut it off just a few seconds earlier.

|

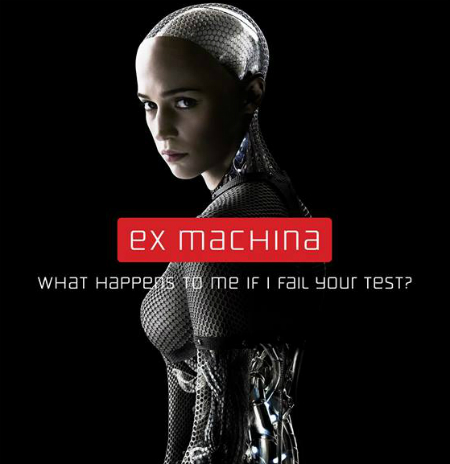

Sterile white rooms, an empty landscape outside, and a vaguely unsettling score give the sense that all is not right with the insulated world into which Ex Machina has brought us, but it also renders our focus on the characters – of which there are basically only four – that much more intense. Future Star Wars castmates Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson are, respectively, alpha-nerd billionaire Nathan, and lowly programmer Caleb, the latter believing he has won a random lottery to spend the week with his CEO at a private Alaska estate. You’ll hardly be surprised that’s not quite the case – he soon finds he’s been rather specifically chosen to help test the artificial intelligence capabilities of a sexy, semi-transparent humanoid robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander).

|

Nathan is apparently a Silence of the Lambs fan – the setup is such that Caleb and Ava are separated by thick glass, with her being confined to chambers, and he occasionally offering personal information to try and get a rise out of her. But when she starts to use power outages to her advantage in order to slip Caleb secret information about Nathan’s real agenda, the plot thickens: is she lying, or is Nathan? Or are both ensnaring Caleb in a bigger plan? Hell, is Caleb even everything he seems to be? There’s plenty of time to let your mind examine every possibility before some of the truth reveals itself – but whether Ava is in fact a new form of consciousness might be unknowable even to the viewer, depending on how you interpret what ensues.

|

I mentioned four characters, though, didn’t I? Filling out the quartet is the ever-silent Kyoko (ballet dancer Sonoya Mizuno), Nathan’s assistant who understands no English – or, at least, so he thinks – in order that she not be able to leak corporate secrets. That there’s more to her is obvious, but what her agenda is may not be.

Isaac, as is often the case, steals the show – though he always does so in a different way, which is nice. Nathan is no Llewyn Davis or Abel Morales, but he is the perfect fusion of the modern “nerd” sensibility fused with macho male archetype. In the ’80s, this beer-guzzling, heavy weight-lifting go-getter would have been beating up computer programmers for being dorks; in the twenty-teens, he has stolen all their stuff and become the best at it, just as easily as the bullies in the old Charles Atlas comics steal the nebbish’s girl on the beach.

|

In turn, his creation in many ways epitomizes the perception of femininity that the contemporary online misogynist-recluse troll has. Ava at times behaves more like what a drunk loner with high testosterone imagines a woman would be like than what one actually is – it’s a subtle thing, but one of the best undertones of Garland’s screenplay. There will inevitably be voices that make accusations of actual misogyny here, but I read it is a critique of same, and a usage of the tropes against both the film’s characters and its viewers’ expectations.

|

While Ex Machina is not heavy on the visual effects, some work better than others – Ava, in her unclothed robotic state, is a wonder of digital replacement, but there are moments I shouldn’t spoil in which certain actions might have been better replicated with practical effects than a too-smooth use of digital. It is in the end more about the ideas than the execution, and certainly most of us have favorite movies in which we forgive effects flaws of a bygone era, so maybe it’s harsh to harp on the minor details. If they take you out of the moment, though, one is entitled to question the choice; fortunately, the actors are strong enough that you believe them even when you question what you see.

Many movies about robots these days almost require a reverse Turing test – you can’t quite believe they were written by humans, rather than number-crunching machines. I’m happy to say Ex Machina would pass.